Imagine standing in a river on a warm July afternoon. The cool water rushes over your boots, and the sound of the wind in the fir trees drowns out the noise of the highway. You reach down into the gravel bar and pull out a stone the size of a golf ball. It looks unassuming at first, perhaps covered in a layer of gray silt or white clay. But then you dip it into the water. Suddenly, it glows. The dull exterior vanishes, revealing a deep, translucent amber light that seems to radiate from within. You have just found a Washington carnelian agate.

Finding these gemstones is one of the most thrilling treasure hunts in the Pacific Northwest. But the story of how that stone ended up in your hand is far more exciting than just a lucky day at the river. It is a story that involves exploding volcanoes, ancient tropical rainforests, and a geological recipe that took millions of years to perfect. To truly appreciate the carnelian agate, we have to take a deep dive into the science of its creation. We have to travel back in time to a Washington state that looked very different from the one we know today.

The Volcanic Recipe for Washington Gems

The story begins with fire.

If you were to visit Southwest Washington about fifty million years ago, you would not need a rain jacket. You would need a pith helmet and plenty of bug spray. During the Eocene epoch, this region was not the temperate, evergreen landscape we see now. It was a subtropical paradise. Palm trees grew where Douglas firs now stand. The climate was warm and humid, similar to what you might find in modern Southeast Asia or Central America.

This was the world that gave birth to our agates. But it was not a peaceful world. The Pacific Northwest has always been a place of violent geology, and the Eocene was no exception. Massive volcanoes were erupting across the landscape. These were not the picturesque, snow capped peaks like Mount Rainier that we admire today. These were rugged, angry vents that spewed countless tons of lava and ash across the land.

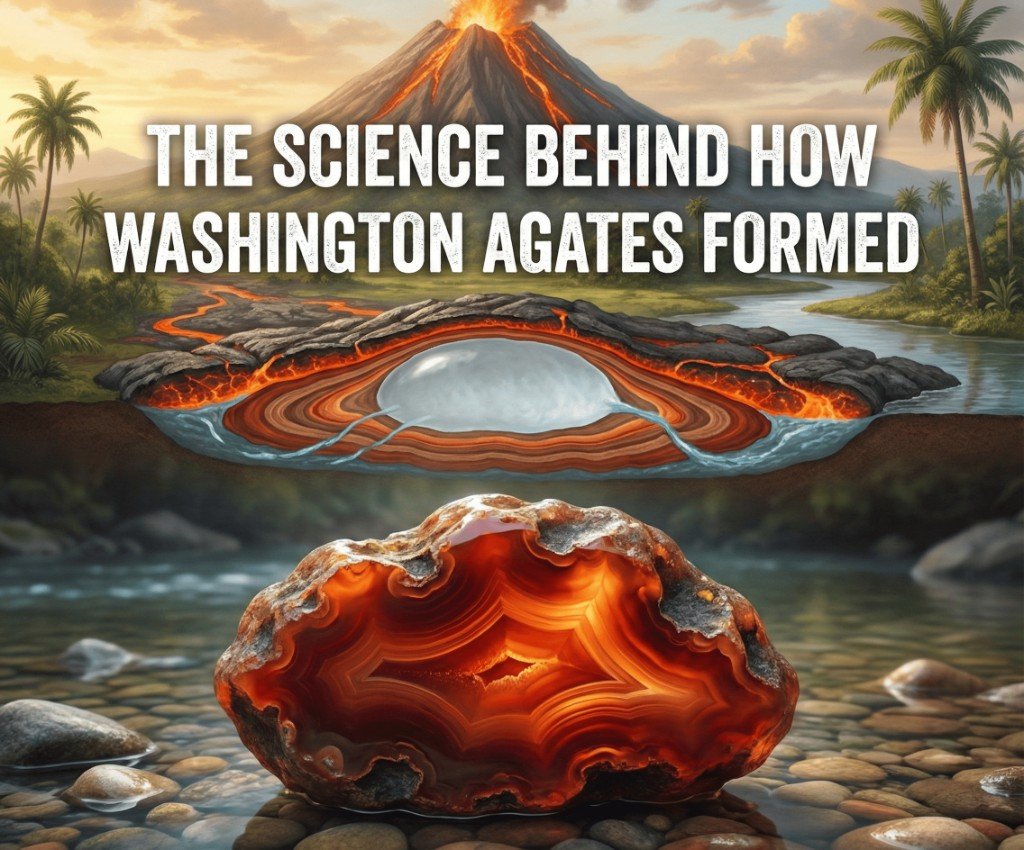

This volcanic activity is the first essential ingredient in the agate recipe. Specifically, we need basalt. Basalt is a type of volcanic rock that forms when lava flows on the surface and cools down. But not just any lava will do. To make an agate, you need lava that is full of gas.

Think of a bottle of soda that has been shaken up. When you open the cap, bubbles rush to the top. Molten rock works in a similar way. It is full of dissolved gases like water vapor and carbon dioxide. When that lava erupts from a volcano and flows across the ground, the pressure drops. The gases try to escape, forming bubbles within the thick, molten liquid.

As the lava cools and hardens into solid rock, those bubbles get trapped. They are frozen in place, creating a Swiss cheese texture inside the basalt. Geologists call these holes vesicles. If you have ever looked at a piece of pumice or scoria, you have seen this on a small scale. For agates, we are interested in the larger vesicles, the ones ranging from the size of a pea to the size of a grapefruit.

These empty pockets are the molds for our future gemstones. Without these gas bubbles, there would be no place for the agate to grow. The rock would just be a solid, boring slab of gray basalt. The vesicle provides the safe harbor where the magic can happen.

However, an empty hole in a rock is not a gemstone. It is just a hole. The next step in the process requires water.

Washington has always been a wet place. In the Eocene, the tropical rains were heavy and constant. Groundwater rich in silica began to percolate through the hardened lava flows. Silica, or silicon dioxide, is one of the most common minerals on Earth. It is the main ingredient in sand and glass.

As this water moved through the ground, it dissolved silica from the surrounding volcanic ash and rock. The water became a silica soup. Slowly, over thousands and thousands of years, this mineral rich water seeped into the gas bubbles trapped deep inside the basalt flows.

This is where the science gets really cool. The conditions inside these vesicles were perfect for precipitation. The water could not hold onto all that dissolved silica forever. As the temperature dropped or the chemistry of the water changed, the silica began to drop out of the solution. It coated the inside walls of the gas bubble.

It did not happen all at once. If it had, you would just have a solid chunk of quartz. Instead, the process happened in microscopic layers. The silica laid down a microscopic film on the wall of the cavity. Then, perhaps the water flow stopped for a season. When it started again, the chemistry might have been slightly different, laying down a new layer that was just a tiny bit different in density or color.

This repetitive process is what gives agates their signature banding. If you cut a fortification agate in half, you can see these concentric rings, looking very much like the rings of a tree. They trace the shape of the original gas bubble, shrinking inward and inward until the entire cavity is filled solid.

Why Washington Agates are Red and Orange

But wait. Most of the agates we find in Lewis County and on the coast are not just clear quartz. They are carnelian. They burn with bright reds, deep oranges, and golden ambers. Where does that color come from?

The answer lies in the name of one of our most famous local features. Iron. The volcanic rocks of Washington are rich in iron. You can see it in the rusty coloring of the basalt cliffs along the Columbia River. As the hot water circulated through the ground, it did not just pick up silica. It also picked up iron oxide.

Iron oxide is just the scientific name for rust. It is the same substance that turns an old truck orange if you leave it in a field for too long. In the world of gemstones, however, rust is a painter.

When trace amounts of iron oxide mixed with the silica gel filling the vesicles, it stained the crystals. A little bit of iron might create a soft yellow or honey color. A higher concentration creates that vivid, lollipop orange that collectors prize. And if the concentration was high and the stone was exposed to natural heat, it could turn a deep, blood red.

This is why Washington carnelian is so special. Our specific volcanic recipe had just the right amount of iron to create these intense, glowing colors. In other parts of the world, agates might be gray or blue because the local rocks had different trace minerals. But here in the Pacific Northwest, we have the Iron Oxide special.

Dinosaurs and the Age of Mammals

Now, let's talk about the dinosaurs.

You wanted to know about dinosaurs. It is a natural question. When we hold a rock that is millions of years old, we want to know if a Tyrannosaurus Rex might have stepped on it.

The answer is a gentle no, but the reality is just as fascinating.

The non avian dinosaurs met their end about sixty six million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period. The lava flows that created our Washington agates are younger than that, generally dating to the Eocene epoch, which started around fifty six million years ago. So, the dinosaurs had already been gone for about ten to fifteen million years when our agates were being born.

However, that does not mean the land was empty. Far from it. The Eocene was the dawn of the Age of Mammals. While our agates were slowly crystallizing inside their basalt tombs, the world above them was teeming with incredible beasts that would look like monsters to us today.

Imagine a creature called a Uintatherium. It looked a bit like a rhinoceros but with six knobby horns on its head and dagger like tusks. These giants roamed the forests of North America during this time. There were also early horses the size of house cats, scurrying through the underbrush to avoid predators.

The rivers where these animals drank were the same rivers that were carving through the landscape, burying the lava flows under layers of sediment. While there were no T Rexes, there were terror birds. These were flightless, carnivorous birds that stood over six feet tall and hunted small mammals. In a way, the dinosaurs were still around, they had just evolved into birds and were terrorizing the early mammals.

So when you hold a Washington agate, you are not holding a rock from the time of the dinosaurs. You are holding a rock from the time when the Earth was recovering from the asteroid impact that killed them. You are holding a witness to the rebirth of life on our planet. It is a gemstone from the era when mammals took the throne.

How Erosion Brings Agates to the River

Let us get back to the geology. We have our gas bubble. We have filled it with silica and iron to make a red gemstone. But right now, that gemstone is still trapped deep inside a massive underground lava flow. It is locked in a prison of basalt. How does it get into the river where you can find it?

This is where the forces of erosion take over.

Basalt is a hard rock, but it is not invincible. Over millions of years, mountains rise and fall. The tectonic plates shift. The Cascade Mountains began to push upward. As the land rose, it was attacked by the elements. Rain, wind, ice, and gravity all went to work on the volcanic rock.

Basalt has a weakness. It is chemically unstable on the surface. When exposed to water and air, the minerals in the basalt begin to break down into clay. The rock rots. It crumbles away.

Agate, however, is made of quartz. Quartz is one of the most durable minerals in the universe. On the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, a diamond is a ten. Agate is a seven. Steel is only about a five or a six. This means that an agate is significantly harder than a steel knife. It is chemically inert, meaning it does not rust or rot.

So, as the host rock around it turns to mud and washes away, the agate remains perfectly intact. It pops out of the crumbling basalt like a seed popping out of a fruit.

Once it is free from the rock, gravity takes over. The agate rolls down the hillside and eventually finds its way into a stream or creek. This is the beginning of its journey to you.

The river acts as a giant, natural rock tumbler. As the agate is swept downstream by the current, it bangs against other rocks. It gets tumbled and ground in the sand.

Remember that the agate is harder than almost everything else in the river. The basalt, sandstone, and shale rocks in the riverbed are much softer. So, while the other rocks get pulverized into sand, the agate survives.

In fact, the river does the agate a favor. The rough, outer skin of the stone is often worn away by this tumbling action. The sharp edges are smoothed down. The natural polish begins to appear. This is why river agates are often round and smooth, feeling perfect in the palm of your hand. They have been processed by the river for thousands of years before you ever picked them up.

The journey of an agate is a long one. It might spend ten thousand years trapped in a gravel bar, buried under ten feet of sediment. Then, a massive flood comes along and moves the gravel bar, releasing the stone again. It moves a few miles downstream and gets buried again. This cycle repeats over and over.

That little stone in your pocket might have been eroding out of the mountain for the last million years. It has seen ice ages come and go. It sat in the riverbed while the Columbian Mammoth, the official state fossil of Washington, walked along the banks. These massive elephants with spiraling tusks roamed our state during the Pleistocene, which was only about twelve thousand years ago. Your agate was already ancient news by the time the mammoths arrived.

It is humbling to think about. We live our lives in minutes and hours. The agate lives its life in epochs and eras.

There is another fascinating aspect to Washington agates that connects to the "Swiss Cheese" theory. Have you ever found a geode? A geode is essentially an agate that did not finish baking.

Remember how the silica layers coat the inside of the gas bubble? Sometimes, the supply of silica runs out before the hole is completely filled. When this happens, you get a hollow center. Often, the final layer of silica will crystallize into macro quartz crystals, forming a beautiful, sparkling cave in the center of the stone.

In Washington, we find these "nodules" or geodes frequently. They are just siblings to the solid agates. One had enough silica to fill up, the other got cut off halfway through the process. Both are beautiful, and both tell the same geological story.

Let us look at some fun facts that you can share with your friends next time you are on a rockhounding trip.

Did you know that Washington is consistently one of the top gem producing states in America? While we do not have diamond mines, the sheer volume of agates, petrified wood, and jade found here puts us on the map.

Speaking of petrified wood, it is the official state gem of Washington. The formation process is very similar to agate. Instead of a gas bubble in lava, the host is a buried log or tree branch. The silica rich water soaks into the wood cells, replacing the organic material with stone. In many cases, the wood is replaced by carnelian agate, creating what we call agatized wood. This is a two for one special: a fossil and a gemstone in one package.

Another fun fact involves the location. The Lewis County Agate Belt is famous, but did you know that glaciers played a huge role in moving rocks around Washington? During the last Ice Age, massive sheets of ice covered the northern part of the state. These glaciers acted like bulldozers, pushing millions of tons of rock from Canada and Northern Washington all the way down to the Olympia area.

While most of our carnelian comes from local volcanic sources, you can sometimes find rocks on Puget Sound beaches that were carried there by ice from hundreds of miles away. It is a geological mixing pot.

The "Science of the Glow" is another great talking point. Why does carnelian glow when you hold it up to the sun? It is because the stone is translucent, meaning it lets light pass through but diffuses it. But the structure of agate is unique. It is made of microcrystalline quartz, specifically a variety called chalcedony. The crystals are so tiny that you cannot see them with the naked eye. They are packed together in fibrous bundles.

When light hits these bundles, it scatters. This scattering effect, combined with the iron oxide pigment, creates that warm, inner luminosity that makes carnelian so attractive. It is literally catching the sunlight and bouncing it around inside the stone before sending it back to your eye.

So, how can you use this science to find more agates?

Understanding the formation helps you hunt. You now know that agates are heavy (specific gravity) and hard. In a river, they will settle in the same places that gold settles. Look for the "drop zones" behind large boulders or on the inside bends of the river. This is where the water slows down and drops its heavy treasures.

You also know to look for color. That iron oxide red is your beacon. In a river filled with gray basalt and white granite, that flash of red or orange is an immediate giveaway.

And knowing that they come from the volcanic foothills, you can look at a map. Find the old volcanic flows in Lewis County. The rivers that drain these areas are your best bet. You are not just looking for a random rock; you are tracking the erosion of an ancient volcanic landscape.

The next time you pick up a carnelian agate, take a moment to really look at it.

Do not just look at the pretty color. Look deeper.

See the gas bubble that formed in a lava flow fifty million years ago.

See the tropical rain that dissolved the mountains to make the silica soup.

See the iron from the rusty earth that painted the layers.

See the millions of years of darkness while the mammals evolved above it.

See the power of the river that broke the stone free and polished it for you.

You are holding a time capsule. It is a piece of the Earth's history, frozen in stone. It is a connection to the volcanoes that built the Pacific Northwest and the ancient world that preceded us.

That little red stone is a survivor. It survived the cooling of lava. It survived the crushing weight of the earth. It survived the erosion of mountains. It survived the tumbling of the river.

And now, it belongs to you.

That is the true value of a Washington agate. It is not just a rock. It is a story. It is a lesson in patience, resilience, and beauty. It is science you can hold in your hand.

So keep hunting. Keep looking at the ground. You never know when the next chapter of geological history will reveal itself to you, shining bright red in the cold, clear water of a Washington stream.